Question:

Is there room for “self-expression” in my wearing of hijab? I see some Muslims condemning hijabi fashion writers, for instance, and I don’t understand why. If my body is covered as it should be, what is the problem with doing it in a way that expresses my personality?

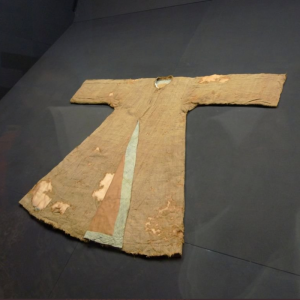

Dress of Sayyida Fatima, held in the Topkapi.

Answer:

The choice of what to wear depends on many factors: the types of clothing available where one lives; the climate there; one’s finances; and what is deemed appropriate in one’s culture. As a Muslim, the first thing one considers when it comes to one’s clothing and outer appearance is: “What is pleasing to Allah?” That is the primary consideration, and all other factors are still taken into account but in a manner secondary to one’s goal of pleasing Him.

TO BE INDISTINGUISHED

If one defines personality as “the combination of characteristics or qualities that form an individual’s distinctive character,”[i] then there is no precedent for using clothing to express one’s personality in the Sunnah of the Messenger of Allah (Allah bless him and grant him peace), regardless of whether one is a man or a woman. In fact, the emphasis is on downplaying one’s distinctiveness unless otherwise necessary. The following ahadith help demonstrate this.

Mu’adh b. Anas (Allah be please with him) related that the Prophet of Allah (Allah bless him and grant him peace) said, “Anyone who, out of humility, shuns fine clothing when they have the ability to wear it will be called by the Almighty on the Day of Judgment before all of creation and given the opportunity to choose whatever garments of faith they would like to wear.”[ii]

Abu Zumayl related that ibn ‘Abbas (Allah be pleased with him) said to him, “When the Haruri tribe revolted, I went to ‘Ali (Allah be pleased with him) and he told me to go to them. So I dressed in the best of my Yemenite clothing and, when we met they said, “Welcome, O Son of ‘Abbas! What clothes are these?” So I replied, “Don’t find fault with me. For, verily, I have seen the Prophet of Allah (Allah bless him and grant him peace) wearing clothes even finer than these.”[iii]

Abu Rimthah (Allah be pleased with him) related that he saw two green garments on the Prophet of Allah (Allah bless him and grant him peace).[iv]

The Messenger of God (Allah bless him and grant him peace) said: “Eat, drink, give charity, and don clothing without arrogance or extravagance, for verily Allah likes that the traces of His blessing be seen upon His slave.”[v]

A lack of excessive attention to one’s appearance was the default state of the Messenger of God (Allah bless him and grant him peace) as well as of his Companions (may Allah be pleased with them). They paid attention and dressed exceptionally when the Shariah called for it, such as when needing to impress one’s enemy. Otherwise, humility and indistinctiveness was what was praised by the Prophet (Allah bless him and grant him peace) such that one who chose to be this way will have the honor of wearing the garments of the highest ranking of the believers in Paradise. Intention is what matters: one does not dress in simple clothing with the intent to show one’s piety, just as one does not dress in fine clothing to show one’s worldly status. As one can see from the second hadith, the practice of the Prophet (Allah bless him and grant him peace) and his Companions (Allah be pleased with them) was “not disregard for their appearance but a lack of attention to such disregard.” It was not that they were trying to be humble. They were humble, and their clothes reflected this. When they did turn to look at how to make an impression, it was for the sake of Allah. This does not mean that they were automatons, all dressed in uniform. Color and style (e.g. Yemenite) varied, but in the words of one hadith commentator, “If they do this [i.e. choose a particular way of dressing] to show off, then it is blameworthy. On the other hand, if they do so out of some practical consideration, like if they find that clothing of one color or another shows less dirt and wears longer, then there is no problem with that.”[vi]

WOMEN’S INDISTINCTIVENESS

Such a lack of attention to distinguishing oneself via clothing is even more important for women due to Allah’s command to them: “Do not display your adornment.”[vii] Women are commanded to cover more in public than what both men and women are required to cover in private.[viii] This relates to the rules of Islam regarding sexual looking. In the Chapter of Light, both men and women are told to lower their gaze, but women are also asked to cover their accessories and to draw their headcoverings over their chests as a way to fully conceal the curves of their bodies. A poetic verse succinctly describes the reason for these rules regarding sexual looking:

نظرة فابتسامة فسلام فكلام فموعد فلقاء

A look, then a smile, then a greeting

Then speech, an appointment, and the tryst[ix]

The rulings of Islam nip the problem in the bud, preventing sexual indiscretion in society by asking men and women not to sexually look (i.e. look with desire or in a way that may create sexual tension) at those who are unlawful for them to touch. The rulings of hijab for women are supplementary to and in support of the “lower your gaze” ruling. The reason given for this in the Qur’an is that they be protected and not be molested.[x]

Modern scientific reasons are given by contemporary Muslims as well, such as that men seem to be more aroused by visual stimuli than women. This would support the Qur’anic justification mentioned above: women who cover would indeed be further protecting themselves in the face of strong male visual inclinations. In addition to this, women’s own sexual arousal is controlled by them covering themselves. A woman’s awareness of her own attractiveness increases her sexual urge.[xi] This is hinted at in the words of the feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir (d. 1986), who celebrates the woman’s power over her own sexual urge: “Every woman drowned in her reflection [i.e. when looking at herself] reigns over space and time, alone, sovereign; she has total rights over men, fortune, glory, and sensual pleasure.”[xii] As Muslims, we recognize this urge, but instead of embracing it unconditionally, we seek to channel it appropriately for the sake of Allah. By covering in public, the Muslim woman helps tame her own desire, as well as that of the men she meets outside her private sphere.

The covering in public required of women is all-encompassing. The scholars of Islam agree that the optimum way for a woman to cover herself is so that nothing shows, that her entire body be covered.[xiii] When Allah Most High commands women to cover their forms so that “they may be recognized (yu’rafna),” the “meaning is not that she be recognized such that it is known who she is.”[xiv] Rather, it means that she be recognized as a woman of respectable status who cannot be easily messed around with.

Just as we saw in the general rule that Muslims should avoid distinguishing themselves in their clothing except for the sake of Allah, the same applies for women and the ruling of covering in public. Women’s covering in public embodies the highest level of indistinctiveness, in that if she covers at the most complete level of hijab, her identity might not be known at all. When she does uncover parts, such as her hands and face, she does so in accordance with the rules of God, in a manner that is dictated by necessity. For example, she may be living in a minority Muslim context in which complete cover would not be acceptable, may pose a danger, and would be more harmful than beneficial for both her and those around her. But the Islamic legal maxim that applies here is, “the exception is dictated according to one’s need.” Just because one may need to expose parts of oneself (and that too, only to the extent allowed by God), this does not mean that the original reason for the ruling on public cover be forgotten. The aim is to not attract attention, to not make apparent one’s charms. Combining this with the general ruling of the Muslim not dressing to show off or distinguish oneself, it becomes clear that a woman should avoid showing personality while in hijab.

THE MODERN PUSH TOWARD SELF-EXPRESSION

As Muslims living in the modern era, we must remain alert to the fact that liberal culture promotes the exact opposite of humility and indistinctiveness. According to the philosopher Baruch Spinoza (d. 1677), individuals persist in being “in order to assert themselves in the world as the individuals they are.”[xv] John Stuart Mill (d. 1873) stated emphatically this right to self-assertion: “In the part which merely concerns himself, his independence is, of right, absolute. Over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign.”[xvi] Feminism—the offshoot of liberalism that in particular promotes a woman’s right to individual freedom—proclaims this right with an extra twist. It assumes that any rule that differentiates between men and women favors men and male status over that of women. If liberal philosophers were only militating against the control of state and church, feminist thinkers wish to break free from this extra level of control, by becoming free from men and male opinion as much as possible, with the assumption that religious rules that differentiate between men and women come from men and not from God.

Liberalism’s emphasis on individual freedom has combined with other historical trends to make women’s clothing a particularly charged and important form of self-expression. Even as late as the 1820s, clothing was by and large still made by hand, and its purchase amounted to 10-20% of a family’s annual income.[xvii] With the Industrial Revolution and the invention of the sewing machine and ready-made clothing, the cost of clothing decreased considerably. This was advantageous to Europe for some time, but as industrialization and increased textile production spread to Asia and beyond, the concern for Europeans was how to sustain the clothing industries within their own borders. “If wages are the single most important cost [in the production of clothing] and low-wage countries can perform the assembly tasks, how can clothing producers remain in Europe and North America, and other high-wage regions? The only solution to this conundrum is not technology but fashion.”[xviii] In Britain and elsewhere, fashion-dominated demand was largely confined to womenswear, and the way the textile industry worked to increase this demand was to build in “ever more sophisticated design and fashion content.”[xix] Clothing thus became more differentiated in design, more readily available, and further curated through the concept of fashion in a manner that would attract the consumer loyalty of women of industrialized nations.

Along with this, fashion was increasingly meant to be publicly displayed, since within secular liberalism power, rights, and freedom came increasingly to be equated with what was public and open, not private, hidden, and off-limits. Western fashion continued to uphold the dichotomy of masculinity and femininity, despite the liberal West’s growing emphasis on equality, but femininity now was equated not with modesty and veiling but mini-skirts and makeup.[xx] Modesty was discounted for many reasons: the move away from Christian values toward a post-Enlightenment concept of freedom; the idea of the covered/hidden/private being equated with weakness;[xxi] and the use of the veil as justification for maintaining colonial control over Muslim lands. So much was in turbulence within the Western mindset that even the concept of “self” was being defined anew, with the “founding father of psychology” defining the self as:

all that the person can call his or her own, not only his body and his psychic powers, but his clothes and his house, his wife and children, his ancestors and friends, his reputation and works, his lands and horses, and yacht and bank account.[xxii]

As should be clear from the above, telling a woman to cover in public eventually became anathema to this whole system of thinking. The same goes for the rule against showing “personality,” a concept that only developed in its present form in the 1930s, by psychologists living in a liberal age that honors the individual and “the combination of characteristics or qualities that form an individual’s distinctive character” like never before. With tremendous economic, political and intellectual pressure to show themselves as free, unique, empowered individuals, it is no wonder that Muslim women today, particularly those living in the West, can no longer appreciate the Islamic value of covering indistinctively.

EMBRACING INDISTINCTION

What this means is that for a Muslim woman today to cover herself in a manner that does not attract attention or show her charms is an act of supreme intention. Its outer reality is one that appears subdued, while its inner reality is replete with strength and willful action—the act of submitting to Allah, regardless of what it takes. Such a woman may very well be counted among the “perfectly obedient slaves of the Merciful”[xxiii]—the ‘ibād al-Rahman—since this glorious honorific is given by Allah to those believers who walk humbly on the earth, “with tranquility, modesty and dignity.”[xxiv] The basic rules of women’s public cover are known and acknowledged widely—that she cover her body, with no more than her face and hands showing. But to do so in a manner that captures not just the rules but also the spirit of hijab requires taqwa, Godfearingness, and is a more subtle matter. Years ago, a pious and learned friend had taught me: “Hijab means to cover oneself in a way that doesn’t show one’s personality.” Each woman must judge and watch carefully over her self and her particular social and cultural circumstances to discern how this can be done in the best and most appropriate manner.

Given the social pressure to do the opposite, it is understandable that we need righteous, like-minded friends and the guidance of the learned to fortify us in the goal of carrying ourselves humbly. And for the deepest level of encouragement, we look to the words of the Prophet Muhammad (Allah bless him and grant him peace) when he told us for whom the Hellfire is forbidden. “It is forbidden for the plain, simple, humble, near one,”[xxv] a description that doesn’t fit well with a person who is boldly trying to assert in the world what makes her self distinctive. In contrast to the words of Mill (and even de Beauvoir) quoted above, real sovereignty belongs to Allah, the Lord of the worlds upon Whom all depend, the One who judges and makes rules for us with perfect fairness and wisdom and loving-care, such that by obeying Him the deepest and most profound felicity can be found in this world and most definitely in the Next. In a sense, the clothing of Muslims during the Hajj pilgrimage is the most apparent display of the Muslim downplaying his self and its distinctiveness in the face of the immensity and absolute glory of God. We in our pilgrim’s clothing are indistinguishable from each other, while that very clothing marks us all as the humble, meek, plain servants of Allah, drawn near to Him on the basis of the purity of our submission.

[ii] Tirmidhi

[iii] Abu Dawud

[iv] Abu Dawud, Nasa’i, ibn Majah, Tirmidhi

[v] Tirmidhi

[vi] For the commentary on the first three ahadith, I have relied on the discussion found in the following text: Thanawi, Ashraf ‘Ali, A Sufi Study of Hadith: Haqiqat al-Tariqa min as-Sunna al-Aniqa, trans. Yusuf Talal Delorenzo, London: Turath Publishing, 2010, p. 197-8.

[vii] Quran, al-Nur, 24:31.

[viii] The minimum requirement for covering in front of one’s spouse and close kin is between navel and knee for both men and women, though of course the Sunnah—the ultimate criteria of decorum and respectability—require one to cover much more than this, whether man or woman.

[ix] al-Sabuni, Muhammad Ali, Tafsir ayat al-ahkam min al-Qur’an, Cairo: Dar al-Sabuni, 1999, vol. 2, p. 108.

[x] “O Prophet! Tell your wives and your daughters and the women of the believers to draw their cloaks over themselves. That will be more conducive for them to be recognized and not molested.” Qur’an, al-Ahzab, 33:59.

[xi] In an oft-cited but not well-authenticated hadith, the blind Companion ibn Umm Maktum entered upon Umm Salamah and Maymuna (Allah be pleased with them both) while they were not in hijab. Once he had entered, they still did not cover themselves. So the Prophet (Allah bless him and grant him peace) told them to wear hijab, and they said, “But he is blind!” to which he (Allah bless him and grant him peace) responded, “Are you both (also) blind, or aren’t you two sighted?” (al-Qurtubi, Muhammad b. Ahmad, Tafsir al-Qurtubi, al-Jami’ li-ahkam al-Qur’an, Cairo: Dar al-Shu’ab, n.d., vol. VII, p. 4620.) The usual commentary given for this is that the Prophet (Allah bless him and grant him peace) was emphasizing their special sanctity, as both women were of the wives of the Prophet (Allah bless him and grant him peace). But could another reason also be that their own sense of chastity would be protected by their covering in front of a man, despite the fact that he could not see them?

[xii] de Beauvoir, Simone, The Second Sex, New York: Vintage Books, 2011, p. 669.

[xiii] The Hanafi, Shafiʿi and Hanbali schools all recommend women to cover their face in public, with some indicating it to be wajib. As for the Maliki school, there is a difference of opinion on the matter. Imam Malik deemed covering the face as being disliked, but later Maliki scholars differed: some said the woman must cover her face entirely, some said she must cover by leaving one eye open, some said she must cover half of her face, and some recommended the men to lower their gaze rather than tell the woman to cover her face. However, it must be noted that this difference of opinion in the Maliki school is with reference to the covering of Muslim women in front of Muslim men. As for covering in front of non-Muslim men, the Maliki school is in agreement with the other schools that women should cover their faces. See: al-Fawākih al-Dawāni ‘ala Risāla ibn Abi Zayd al-Qayrawāni. (My thanks to Ustadha Mona Elzankaly for the information and reference regarding the ruling in the Maliki school.)

[xiv] al-Qurtubi, Tafsir al-Qurtubi, vol. VIII, p. 5326.

[xv] Gray, John, Liberalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995, p. 11.

[xvi] Mill, John Stuart, On Liberty, Simon & Brown, 2011, p. 12.

[xvii] Godley, Andrew, “The Development of the Clothing Industry: Technology and Fashion,” in Textile History, 28:1, p. 5.

[xviii] Ibid., p. 7.

[xix] Ibid., p. 8.

[xx] Selby, Jennifer A. and Fernando, Mayanthi, L. “Short Skirts and Niqab Bans: On Sexuality and the Secular Body,” September 4, 2014, http://tif.ssrc.org/2014/09/04/short-skirts-and-niqab-bans-on-sexuality-and-the-secular-body/ [Last accessed: July 8, 2020].

[xxi] For an illuminating overview of the various ways in which the dichotomy of public vs. private appears within modern Western thought, see Weintraub, Jeff, “The Theory and Politics of the Public/Private Distinction” in Weintraub, Jeff and Kumar, Krishan, Public and Private in Thought and Practice: Perspectives on a Grand Dichotomy, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1997, p. 1-42.

[xxii] William James (d. 1910), as quoted in Carolyn Mair, The Psychology of Fashion, Milton Park (UK): Routledge, 2018.

[xxiii] Shafi, Muhammad, Ma’ariful Qur’an: A Comprehensive Commentary on the Holy Qur’an, trans. Muhammad Ishrat Hussain, Karachi: Maktaba-e Darul-‘Uloom, 2005, 6:509.

[xxiv] Commentary on Qur’an, al-Furqan, 25:63, as found in ibn ‘Ajiba, Ahmad, al-Bahr al-Madid fi Tafsir al-Qur’an al-Majid, Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-‘Ilmiyya, 2010, 5:145.

[xxv] As cited in al-Darqawi, al-‘Arabi, The Darqawi Way: The Letters of Shaykh Mawlay al-‘Arabi ad-Darqawi. Trans. ‘Aisha ‘Abd al-Rahman at-Tarjumana. Cambridge: Diwan Press, 1979, p. 236.